The Damselfly:

The Damselfly: A Delicate Predator of the Pond

Fast Facts

The Blue-Ringerd Dancer Damselfly (Argia sedula)

Name: Damselfly (Odonata order: Zygoptera suborder)

Number of Species: Over 21 genera and nearly 300 species in North America, with over 3,000 species worldwide

Range: Found near ponds, lakes, marshes, and rivers throughout North America

Size: Small: Usually from 1 - 2 inches (2.5 to 5 cm) in length

Dragonfly lookalikes: Unlike dragonflies, damselflies are slim and hold their wings closed over their bodies when at rest

Skilled Predators: They are agile flyers and skilled hunters of small insects

Damselfly larvae: Larvae (nymphs) live underwater and are important aquatic predators

Conservation Status: Many damselfly species are stable, but some face threats from habitat loss and water pollution.

How to Support Damselflies: Provide a wildlife pond with native aquatic plants for shelter and breeding.

Fun Fact: During mating, damselflies form a heart-shaped pose known as the "mating wheel"—a distinctive and charming behavior unique to the order Odonata.

The Damselfly: A Delicate Predator of the Pond

An image of two damselfies: Left: Common Blue Damselfly (Enallagma cyathigerum) and Right: Blue-tailed Damselfly (Ischnura elegans).

Introduction

Damselflies are among the most graceful and mesmerizing insects found near ponds, wetlands, and slow-moving streams. With their slender bodies, shimmering wings, and iridescent colors, these aerial acrobats are a joy to watch and an important part of wetland ecosystems.

Though often overshadowed by their larger and more robust relatives, the dragonflies, damselflies are just as fascinating. Their presence in your backyard pond or natural water feature not only signals a healthy ecosystem but also supports the food web, serving both as predator and prey.

Description

Damselflies are typically smaller and more delicate in appearance than dragonflies. They have long, thin abdomens and two pairs of transparent wings. When perched, damselflies hold their wings folded neatly over their back, unlike dragonflies which rest with wings outstretched. Their large compound eyes are set wide apart, giving them excellent vision to spot small flying insects.

Coloration varies widely, but many damselflies display iridescent blues, greens, and even purples. These colors often shift with the angle of light, making damselflies appear to shimmer as they dart through the air.

Damselfly vs. Dragonfly:

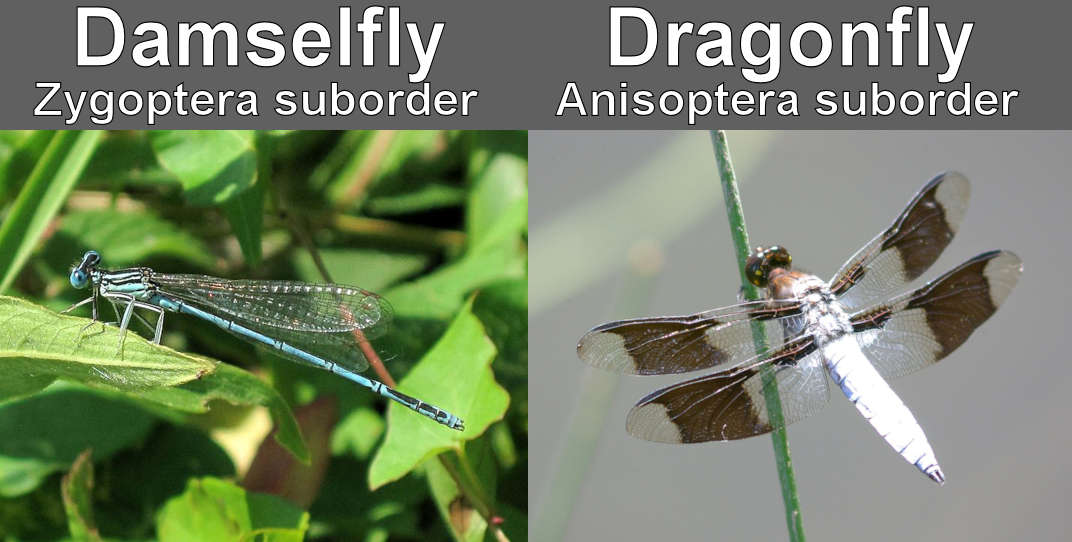

A damselfly vs a dragonfly. Both are in the Odanata Order, but are in different suborders. Damselflies are in the Zygoptera suborder and Dragonflies are in the Anisoptera suborder.

What’s the Difference? While both belong to the order Odonata, damselflies (Zygoptera) and dragonflies (Anisoptera) have several key differences. Damselflies are generally more slender and hold their wings closed or slightly open above their bodies when at rest. In contrast, dragonflies are often larger, bulkier, and keep their wings spread open when perched.

Another key difference lies in their eyes. Damselfly eyes are separated on each side of the head, while dragonfly eyes are much larger and often touch at the top of the head. Their flight styles also differ: damselflies fly with a fluttering motion, whereas dragonflies exhibit more powerful, darting flight.

Habitat and Life Cycle

Bluet damselflies in thier heart shaped mating position.

Damselflies thrive in and around freshwater habitats. Still or slow-moving waters like ponds, marshes, and streams are essential for their breeding. Adults lay eggs on aquatic plants or directly into the water. After hatching, the larvae, known as nymphs, live underwater for several months to over a year, depending on the species.

Aquatic Nymph Stage: Nymphs are predatory and feed on mosquito larvae, small freshwater crustaceans, and other small aquatic invertebrates. They have extendable jaws that shoot out to snatch prey with impressive speed. As the nymphs grow, they molt several times before crawling out of the water and emerging as winged adults.

Adult Stage: Once airborne, adult damselflies continue to prey on small insects such as mosquitoes, gnats, and flies. They are most active during warm, sunny days and often patrol the edges of ponds in search of mates and food.

Males have a pair of claspers at the tip of the abdomen called cerci and paraprocts. These help them grasp the female behind her head during mating. Mating often involves a heart-shaped position known as the "wheel," after which females deposit eggs in or near water.

_nymph-web.jpg)

Blue-tailed damselfly (Ischnura elegans) nymph. Image Credit: Charles J. Sharp CC BY-SA 3.0

Seasonal Appearance and Diversity in Eastern North America

Damselflies are typically seen from late spring through early fall. Their activity peaks during warm summer months, making this the best time to observe their behaviors and striking colors. There are well over 100 species of damselflies in Eastern North America, spread across several genera. Some of the most common and recognizable groups are briefly discussed below and images of many of these groups are seen throughout this article:

Bluets (Enallagma sp.): With over 30 species in the Eastern United States, they are often bright blue with black markings, commonly seen around ponds. The Familiar Bluet (E. civile) is one of the most common bluets.

Forktails (Ischnura sp.): Small and often found in garden ponds, they have a forked terminal appendage (at the end of their tails). The Eastern Forktail (I. verticalis) is especially common.

Spreadwings (Lestes sp.) Known for holding their wings partly open when at rest, unlike most damselflies.

Jewelwings (Calopteryx sp.): Have metallic green or blue bodies and dark, often partially black wings. The Ebony Jewelwing (C. maculata) is one of the more common Jewlwings in eastern North America.

Dancers (Argia sp.): More robust damselflies that are often bluish or purplish in color.

Sprites (Nehalennia sp.): Tiny damselflies that inhabit marshy and vegetated ponds

Rubyspots (Hetaerina sp.): Featuring reddish wing bases and metallic bodies, more common in southern and central regions. The American Rubyspot (Hetaerina americana) is one of the more common Rubyspots in North America.

_(9-16-13)_patagonia_lake,_scc,_az_(9779369705).jpg)

The American Rubyspot (Hataerina americana). Notice the red color at the base of the wings. American Rubyspots become more common toward the end of summer.

Wildlife Value and How to Attract Damselflies to Your Property

Damselflies are excellent natural pest controllers. Both adults and nymphs feed on mosquitoes and other insect pests. They are also a food source for birds, frogs, fish, and other predators, making them an integral link in the food web.

To attract damselflies, create or maintain a clean water source such as a pond with native aquatic vegetation. Avoid chemical pesticides and provide plants both in and around the water to offer perching and egg-laying sites. Even a small backyard pond can become a haven for damselflies and other beneficial wildlife.

Conservation Considerations

Like many aquatic insects, damselflies are sensitive to water pollution, habitat destruction, and pesticide use. Urban development and agricultural runoff can degrade the quality of freshwater environments they depend on. Maintaining or restoring native vegetation and avoiding chemical use in your yard can significantly improve conditions for damselflies and other wildlife. Protecting wetland areas and participating in citizen science efforts also contribute to broader conservation goals.

By welcoming damselflies to your yard, you not only enjoy their mesmerizing beauty but also contribute to a thriving and balanced ecosystem.

Elegant Spreadwings (Lestes inaequalis) captured in their mating pose. Native to eastern North America and Canada, they remain common in some areas but are declining in others due to habitat loss.

The Ebony Jewelwing Damselfly (Calopteryx maculata) is one of the more common Jewelwings in eastern North America.

References

Paulson, Dennis R. Dragonflies and Damselflies of the East. Princeton University Press, 2011.

Lam, Ed. Damselflies of the Northeast: A Guide to the Species of Eastern Canada and the Northeastern United States. Biodiversity Books, 2004.

Kalkman, Vincent J., et al. “Global Diversity of Dragonflies (Odonata) in Freshwater.” Hydrobiologia, vol. 595, no. 1, 2008, pp. 351–363. Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-007-9029-x.