Paleontology News

Life reconstruction of the giant Jurassic ichthyosaur Temnodontosaurus, highlighting the winglike flipper and the unusual structures observed in the fin. Artwork by Joschua Knuppe. Right: Photograph of Drs Lomax and Lindgren, together with fellow researcher Sven Sachs, examining one part of the flipper at Lund University, Sweden. Courtesy of Katrin Sachs

Reconstructing the Silent Hunter: New Clues from an Ichthyosaur Flipper

A newly discovered Temnodontosaurus flipper fossil reveals that this giant Jurassic marine reptile evolved silent-swimming traits to hunt in darkness, offering insights into its behavior and anatomy.

Summary Points

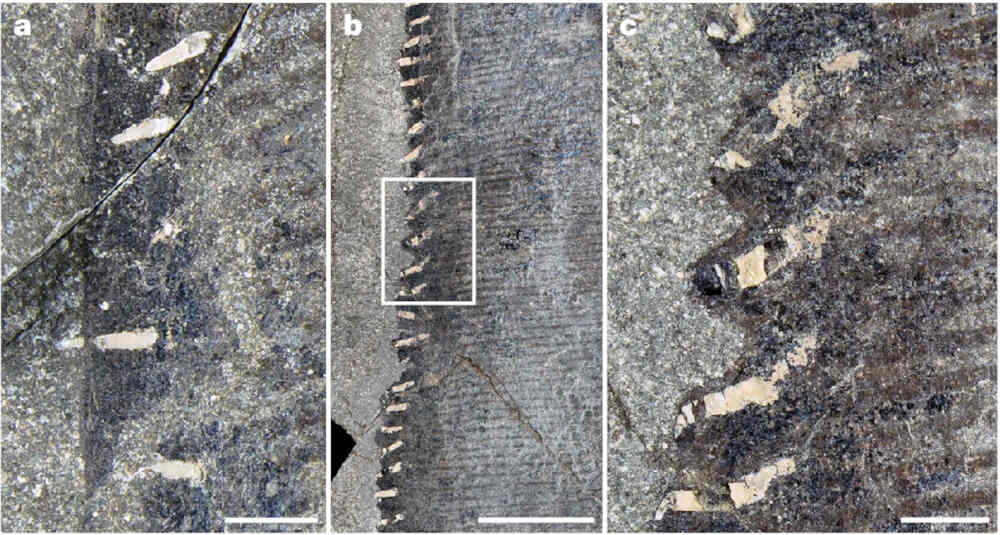

Figure 3 A, B, and C from Lindgren et al. 2025 showing the ichthyosaur flipper with the chondroderms that make up the serrated edge: CC By 4.0

A fossil flipper shows Temnodontosaurus evolved to swim silently, likely for hunting in dark or deep waters.

The flipper's shape, serrated edge, and unique "chondroderms" likely reduced movement noise—like owls in flight.

This ichthyosaur had football-sized eyes, supporting a stealthy, low-light hunting strategy.

Discovered by Georg Goltz in Germany, it's one of the best-preserved soft-tissue ichthyosaur fossils.

Researchers used advanced scans and molecular tools to study the flipper's structure and movement.

The discovery may help design quieter marine tech to reduce underwater noise pollution.

Reconstructing the Silent Hunter: New Clues from an Ichthyosaur Flipper

This article is based on a new release by The University of Manchester, and the Journal Article (Lindgren et al. 2025) from Nature.

A groundbreaking fossil discovery has revealed that a giant marine reptile, Temnodontosaurus, used stealth to hunt prey in dark or deep waters during the Early Jurassic period, around 183 million years ago. This ichthyosaur, over 10 meters long, had specialized flippers that appear to have evolved to reduce noise while swimming—much like the silent flight of owls.

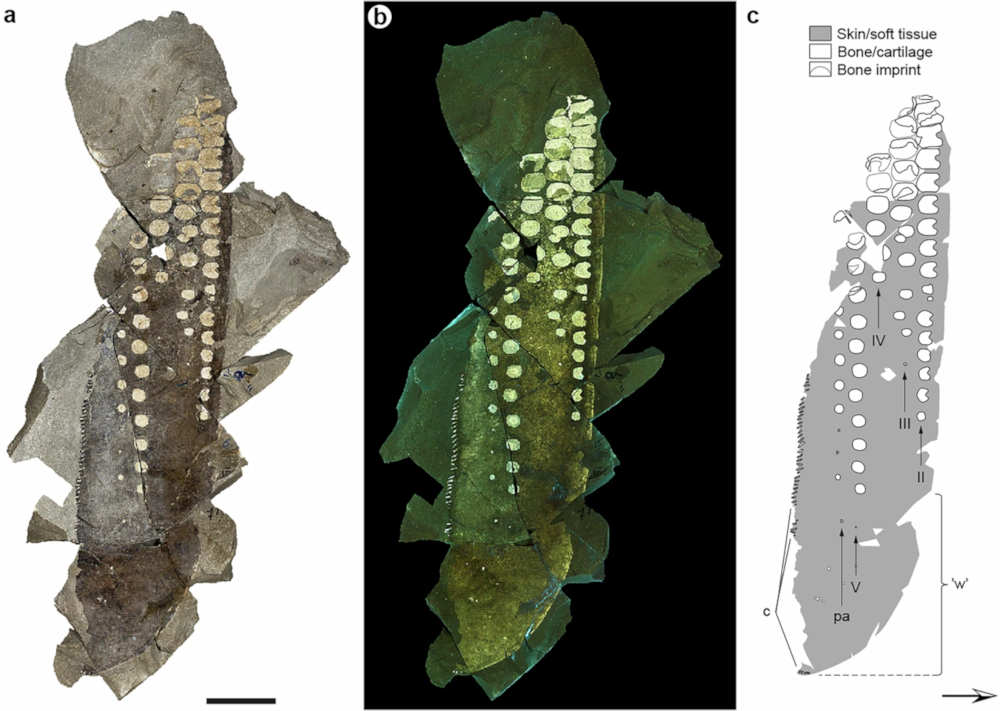

Published in Nature, the study centers around a remarkably preserved fossilized front flipper with soft tissue intact. Researchers led by Dr. Johan Lindgren of Lund University, along with Dr. Dean Lomax from the University of Manchester, believe the flipper's wing-like shape, lack of bones at the distal end, and serrated trailing edge reduced underwater sound during movement—an adaptation never seen in aquatic animals, extinct or living.

Advanced techniques, including chemical and structural analyses and 3D fluid dynamics simulations, revealed unique features in the flipper, including zigzag-shaped edges and previously unknown rod-like structures called "chondroderms." These features likely helped the animal glide silently, enhancing its ability to ambush prey under low-light conditions.

Temnodontosaurus is already known for having the largest eyes of any vertebrate—about the size of footballs—which supports the theory that it hunted at night or in the deep sea. According to Dr. Lomax, who has studied thousands of ichthyosaurs, this specimen stands out as one of the most significant fossil finds ever made.

The fossil was discovered by chance in Dotternhausen, Germany, by collector Georg Goltz, who found both parts of the nearly complete flipper in a road-cut exposure. Though he searched for more, no other remains were found, and the researchers suspect the flipper may have been severed by another ichthyosaur.

The find holds paleontological value and it could also be used in modern conservation. Dr. Lindgren pointed out that understanding how this ancient reptile moved silently through water might inspire solutions to reduce the impact of human-made underwater noise, such as that from ships, sonar, and wind farms.

The fossil was analyzed by a diverse team of experts using cutting-edge tools like synchrotron imaging and infrared microspectroscopy, allowing the researchers to uncover details invisible to the naked eye. Their collaborative approach helped paint a clearer picture of both anatomy and behavior.

The discovery also carries historical significance. The first Temnodontosaurus fossil was brought to science over 200 years ago by Mary Anning and her brother Joseph. Dr. Lomax sees a poetic connection, saying this new find reflects how paleontology continues to build upon the foundations laid by early pioneers like Anning.

Extended Data Figure 1 from Lindgren et al. 2025 showing the ichthyosaur flipper with the preserved tissue: CC By 4.0

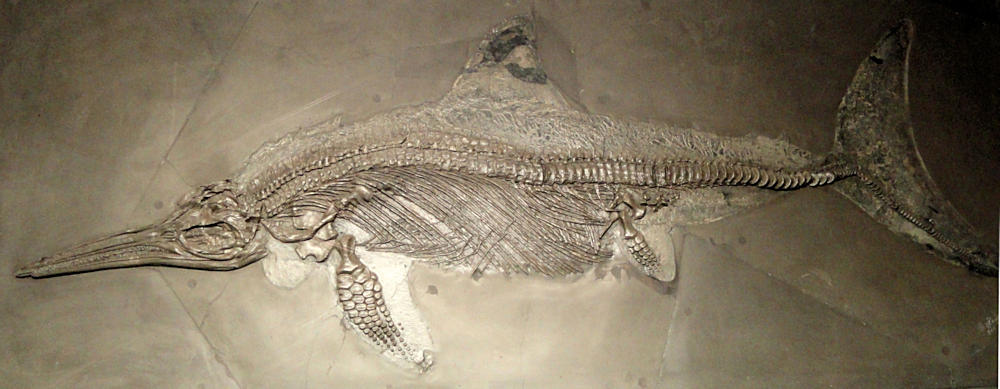

This is an image of a nearly complete ichthyosaur skeleton with soft tissue outline on display at the Senckenberg Natural History Museum in Frankfort, Germany. Public Domain.

Journal Article:

Lindgren, J., Lomax, D.R., Szasz, RZ. et al. Adaptations for stealth in the wing-like flippers of a large ichthyosaur. Nature (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09271-w.

Recommended Dinosaur Books and Educational Items:

Ammonite Fossils by Fossilera